A Professorial Aspie

In the beginning to student life.

A Professorial Aspie - in the beginning

My name is Jacky and the journey isn’t mine but I consider myself fortunate to be a part of it - Simon’s amazing journey from boy to manhood. Simon is my youngest of four boys and this child, from the outset was both wonderful and wanted. His life was not the life we had hoped for but he has, and continues to, surpassed our expectations. Being a ‘Professorial Aspie’ (my words) doesn’t detract from a life of stark contrasts which include amazement and laughter too.

Simon has always been the unintentional comedian and has spent many years creating havoc and ‘dropping himself (and us) in ‘it’’ on a regular basis. On one occasion, when Simon and I were interrupted while out shopping in our local town centre, a gentleman approached and asked if I could advise him whether the local ‘Super-Drug’ shop was nearby. Before I could respond, Simon had moved in front of me – spread his arms and spoke with words of authority. ‘I’m sorry but we don’t ‘do drugs’ at our house – we cannot help you.’ The gentleman concerned looked nonplussed while I gently advised him that I couldn’t help him as I didn’t know the locality of the shop. Once I had explained the situation Simon demonstrated with a factual response – ‘then it’s a silly name for a shop, isn’t it?’ I couldn’t argue.

At age 8 Simon broke down in the local supermarket. Crying, he asked ‘what is wrong with me?’ He needed answers. Throughout the preceding years Simon had experienced many tricky situations, he felt he was ‘tortured’ in school (he had found the definition and considered it appropriate to his experience), he had yet to manage a full night sleep, he didn’t have any friends and he couldn’t understand why.

As his parents, we had been advised that we shouldn’t pre-empt the assessment and possible diagnoses and we felt constrained. But just at that moment I didn’t have anything to tell him, other than the truth. I explained that there was a ‘way of thinking’ that was different than in most people (a little like different computer languages), and that we were investigating if this was a way to understand Simon’s experiences. I called it Autism because at that point, I didn’t want to use the words ‘condition’ or ‘disorder’ and I still believe them to be unhelpful. His response was perfect – he said, ‘so it isn’t my fault?’ He stopped crying and we didn’t discuss it again until his diagnosis a few months later.

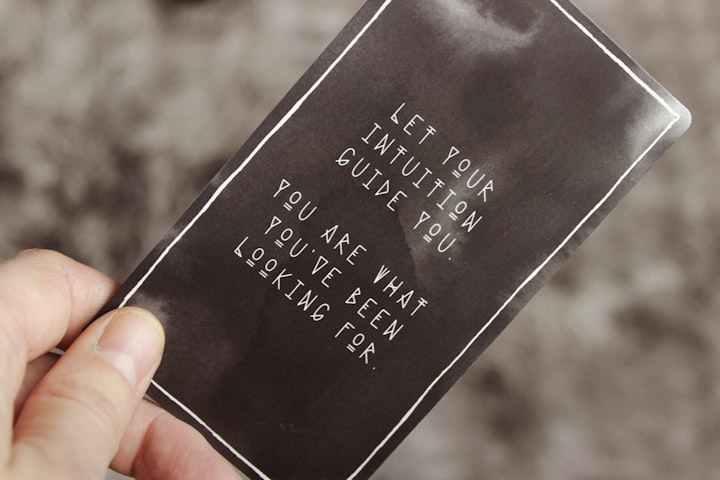

For a young person to become aware that they don’t ‘fit the pattern’ but have no explanation can result in immediate ownership ‘for’ the problems they face. This does not reflect the spectrum of difficulties or range of capabilities within Autism, but it is helpful to understand how the uncertainty can negatively impact upon an ability to manage expectations, hopes and dreams. A few years later Simon was to utter the words below – his insight at such a youthful age shouldn’t have been a surprise given all that I knew about him, but he continues to surprise me to this day.

'If there were more people with autism and less people without – I would be neurotypical and you would be the one with a developmental disorder.’

Simon Alty aged 11.

As I type, Simon has just completed his second year at University studying Theoretical Physics. His achievement is more poignant when you consider that he has received multiple diagnoses within the remit of Developmental Disorders – including but not limited to, Autistic Spectrum Disorder (Asperger Syndrome) and Hyperkinetic Disorder…alongside the more mundane hearing impairment.

The difficulties that we, his parents experienced were little in comparison to those faced by Simon and we struggled emotionally and mentally. As for Simon, he continues to work through difficulties to achieve what his capabilities and context allows. I should say that Simon (like each one of us), is a work in progress and what I hope to convey is nature of the journey – complete with mistakes and potential. The journey can become a thrilling observational ride for parents who are have in the past been consistently confronted by the problems of their child ‘not quite fitting in.’

This journal is an instinctive response to the journey we have taken – lessons learned in preparing Simon for University and the ‘anecdotal illustrations’ Simon has provided during his first year ‘living independently’ and in which he has agreed for me to share.

I hope that our journey will offer resonance for some and an increased awareness for others, of the issues that will require attention before, during and after your own ‘Professorial Aspie’ leaves home to attend University. I hope that this can also be used by professionals who are in that unique position to offer hope when sometimes all that a parent can see is a future without and by parents too for whom the journey will have some resonance.

Indulge me as I confess that during my career Simon has been a major influence. I began nurse training in 1992 and at my interview they asked whether I saw myself in any speciality – I replied not but that I knew I didn’t want to work with children or in mental health.

Fast forward through years working in Adult Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting my final position allowed me to work within Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS), specifically with young people affected by ADHD and Autism, and their families. I simply wanted to offer support to other families as they travelled their own journey and I recognised this as a privilege through which I continued to learn throughout my employment and beyond that as I left the NHS in 2015.

Reminiscing…

In college Simon was assigned a project (along with his class members), entitled ‘how to deal with a stress-filled parent.’ Simon produced a written piece of work which, to this day makes me smile and won him praise within his class – the tutor recognised his work was of high quality and copied the structure as a format for others to mirror – analytical and objective (two strengths of his). I had failed to appreciate the inductive nature of his reasoning however and when I read the piece of work (not having been aware of the context) I asked where he had sourced it…Simon was most indignant!

It is interesting that during the diagnostic process and with the overwhelming familiarisation required of a condition, the result is usually the minimisation of strengths. I found that the landscape improved the more I observed Simon developing. I was free to notice unexpected landmarks and topographical variations in what I had been taught to expect. The rigidity of the diagnostic criteria cries out for the expression of negatives – it is essential that we express the difficulties a child/young person faces in order that the impact is recognised and ‘where warranted’ a diagnostic label applied. For lengthy periods of time this, by necessity, skews the vision of the present and the future for our children – only when that part of the journey is complete are we free to dream.

I feel it is only right to say that I am not an expert on anyone else’ child – nor on my own. I have learned much from Simon and he is gracious enough to continue to use me as a resource…

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.